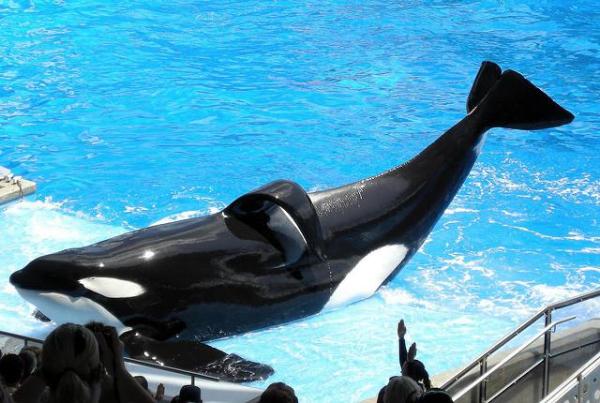

There is an appeal to looking at orcas in captivity. Killer whales are beautiful creatures with a grace and intelligence that is a wonder to behold. To be up close to them can create a sense of awe unlike any other. As playful animals, they can also create great joy, especially for young spectators who see their shows in theme parks across the world. They can even inspire a love of nature which helps us in efforts for conservation. Despite these positive aspects, there is much controversy surrounding captive orcas. The issue of collapsed dorsal fins in killer whales helps us to explain why.

At AnimalWised, we ask why do orca fins bend in captivity? By answering the question, we can look at the issue of how captivity affects the welfare of killer whales and what should be done about it.

Physical characteristics of orcas

Before we look at why orca fins droop, we need to learn more about Orcas (Orcinus orca) in general. Although they are also called killer whales, they are actually part of the family Delphinidae. This is a group of aquatic mammals also known as oceanic dolphins. Their beautiful black and white markings set them apart from other types of dolphin species, as does their size and reputation for being a particularly intelligent and deadly predator.

The maximum body length of orcas is around 9 m/29.5' in males and 7.7 m/25' in females. As sexually dimorphic animals, males develop much larger fins than females, including their pectoral, tail and dorsal fins. In fact, male orcas have the largest dorsal fin of any marine mammal with some measuring as tall as 1.8 m/6' in height. Newborn orcas weigh around 200 kg/440 lb at birth, measuring 2-2.5 m/6.5-8' in length.

As stated above, one of the most recognizable aspects of orcas is their coloration. They are normally black on the dorsal area and white on their underside. They have white elliptical spots around their eyes and a gray spot at the base of the dorsal fin known as the ‘saddle patch’. In newborns, the white areas are an orange color and they do not have a saddle patch during the first year of life.

Orca dentition is quite different from other odontocetes (suborder of cetaceans to which killer whales belong). Their teeth can reach up to 10 cm/4" in length. When their mouths are closed, their upper and lower teeth intersect, resulting in a jaw that is wider than other odontocetes.

Although there is only one recognized species of orca, there is a taxonomic discussion about creating more subspecies. This is because orcas from different parts of the world have certain differences, including in their coloration. The morphological, ecological and ethological differences that exist between the different populations are so diverse that many experts believe the taxonomy of this group should be reviewed.

A curious fact about captive orcas is that females tend to be larger than males up to the age of 6 years. This is contrary to wild orcas. From this, we can see that being held in captivity has an effect on orca development and, by extension, well-being. We look into more detail below about the various repercussions of keeping captive killer whales.

Learn more about other types of aquatic mammals in our related article.

Orca dorsal fins in the wild

According to various studies, the fins of killer whales can have several functions[1][2]. They are incredibly hydrodynamic, meaning they are very swift through the water. This is one of the reasons they are such adept hunters, often chasing very fast prey over long distances.

An orca's fins are also thought to be useful in thermoregulation. Although they generally prefer cooler waters, the habitat distribution of killer whales is the largest of any animal other than humans. Especially if they have been very active, they can use their fins in warmer waters to cool themselves down by moving the water around them.

The fins of orcas are also sexually dimorphic. Males have a larger dorsal fin than females which sits straighter on their body. Females have a smaller dorsal fin which is curled slightly backwards. Despite this slight curling at the tip, the dorsal fins of wild orcas tend to stand up straight in the air. It is rare for wild orca fins to droop, so why do captive orcas' dorsal fins collapse?

Why do captive orca dorsal fins collapse?

We do not know exactly why orca dorsal fins bend in captivity, but we do know that it happens considerably more than in the wild. The reason an orca's dorsal fin folds over is due to deterioration in collagen, the substance which makes it erect in the first place. It is the underlying cause of this deterioration which is difficult to determine, but there are three main theories:

- Overheating of collagen: when held in captivity, orcas do not have the ability to dive very far. This means they spend a lot of their time at the surface of the water with prolonged sun exposure. This is exacerbated by the fact most waterparks are in areas with hot climates. This exposure to the sun heats up the dorsal fin and causes it to bend due to a breakdown in collagen.

- Low blood pressure: another limitation of the tanks in which captive orcas live is their inability to move far or swim very fast. These reduced activity levels means they are not getting the exercise they would in the wild, something which affects their blood pressure and may result in a droopy or bent dorsal fin. Other factors such as improper diet in captivity may contribute to this issue.

- Stress: whether due to dietary changes, lack of exercise or the simple fact that they are incarcerated, many orcas experience stress when in captivity. It is believed that this stress can cause their dorsal fins to collapse.

Although it occurs much more in captivity, orca dorsal fins do sometimes bend in the wild. The reasons for this are also not always clear. It can be due to trauma such as when being hit by a boat passing overhead. There have also been some reports of areas with higher incidences, but these are nothing compared to in captivity. Most captive male killer whales and some females have a collapsed dorsal fin.

Learn more about orca behavior with our article on what killer whales eat.

What does a bent dorsal fin mean for orcas?

While the dorsal fins of orcas do serve a purpose, there does not seem to be much direct harm to the animal when one collapses. They are still able to swim and carry out their basic animal functions. In the wild, the bent fin will mean the orca is less hydrodynamic, but it won't necessarily slow them down significantly. In captivity, their movements are already limited.

The issue with a collapsed dorsal fin in orcas is that it is a signifier of poor treatment. Although most orca trainers undoubtedly love the animals they train, the evidence of the harm captivity causes them cannot be negated. From the very beginning, capturing orcas and keeping them in water tanks has been problematic to say the least. Many of the first specimens did not survive for very long at all.

Looking at the life expectancy of wild versus captive killer whales, we can see an extraordinary statistic. Of the 70 or so orcas born in captivity between 1977 and 2019, none managed to live longer than 30 years. In the wild, orcas commonly have a lifespan of 50-80 years of age. Many other animal species thrive in captivity and generally live longer due to a lack of predation. For orcas, the evidence is clearly to the contrary.

When orca fins bend in captivity, it is because they have restrictions placed on them that harm them both physically and emotionally. There may be times when an orca needs medical help or rehabilitation, but this does not mean we should actively seek to keep them in pools which drastically reduce their quality of life. It is cruel to take orcas out of their natural habitat for purposes of our entertainment. A bent dorsal fin is a stark reminder of this.

If you want to read similar articles to Why Do Orca Fins Bend in Captivity?, we recommend you visit our Facts about the animal kingdom category.

- Cabana, J. (2016). Why do whales have fins?. Retrieved from:

https://baleinesendirect.org/en/what-purpose-do-fins-serve-in-whales - Sea World of Hurt. (n.d.). 8 Reasons Orcas Don’t Belong at SeaWorld. Retrieved from: https://www.seaworldofhurt.com/features/8-reasons-orcas-dont-belong-seaworld

- Clark, S. T., & Odell, D. K. (2013). Allometric relationships and sexual dimorphism in captive killer whales (Orcinus orca). Journal of Mammalogy, 80(3), 777-785.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1383247 - Clark, S. T., Odell, D. K., & Thadlacina, C. (2000). Aspects of growth in captive killer whales (Orcinus orca). Marine Mammal Science, 16(1), 110-123.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2000.tb00907.x - Ford, J. K. B. (2018). Killer Whale: Orcinus orca. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third Edition), 531–537.

https://doi.org/10.1016/C2015-0-00820-6 - Jett, J., & Ventre, J. (2012). Orca (Orcinus orca) captivity and vulnerability to mosquito-transmitted viruses. Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology, 5(2), 9–16.

- Visser, I. N. (1998). Prolific body scars and collapsing dorsal fin are killer whales (Orcinus orca) in New Zealand waters. Aquatic Mammals, 24(2), 71-81.