Different Types of Squid

Squids come in many shapes and sizes, from the Giant squid stretching 13 meters (43 feet) to the Pygmy squid barely reaching 2 centimeters (0.8 inches). These sea animals live in different parts of the ocean, each adapted to its own environment. Scientists keep learning new things about how squids live and behave. Each species has found its own way to survive, whether in deep, dark waters or in shallow coastal areas.

In the following AnimalWised article, we look twelve different squid species. We'll explore where they live, how they hunt, what makes each one different, and how they cope with changes in the ocean.

- Giant squid (Architeuthis dux)

- Colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni)

- Common squid (Loligo vulgaris)

- Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas)

- Vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis)

- Pygmy squid (Idiosepius pygmaeus)

- Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus)

- Luminous squid (Watasenia scintillans)

- Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidea)

- Umbrella squid (Histioteuthis bonnellii)

- Glass squid family (Cranchiidae)

- Arrow squid (Nototodarus sloanii)

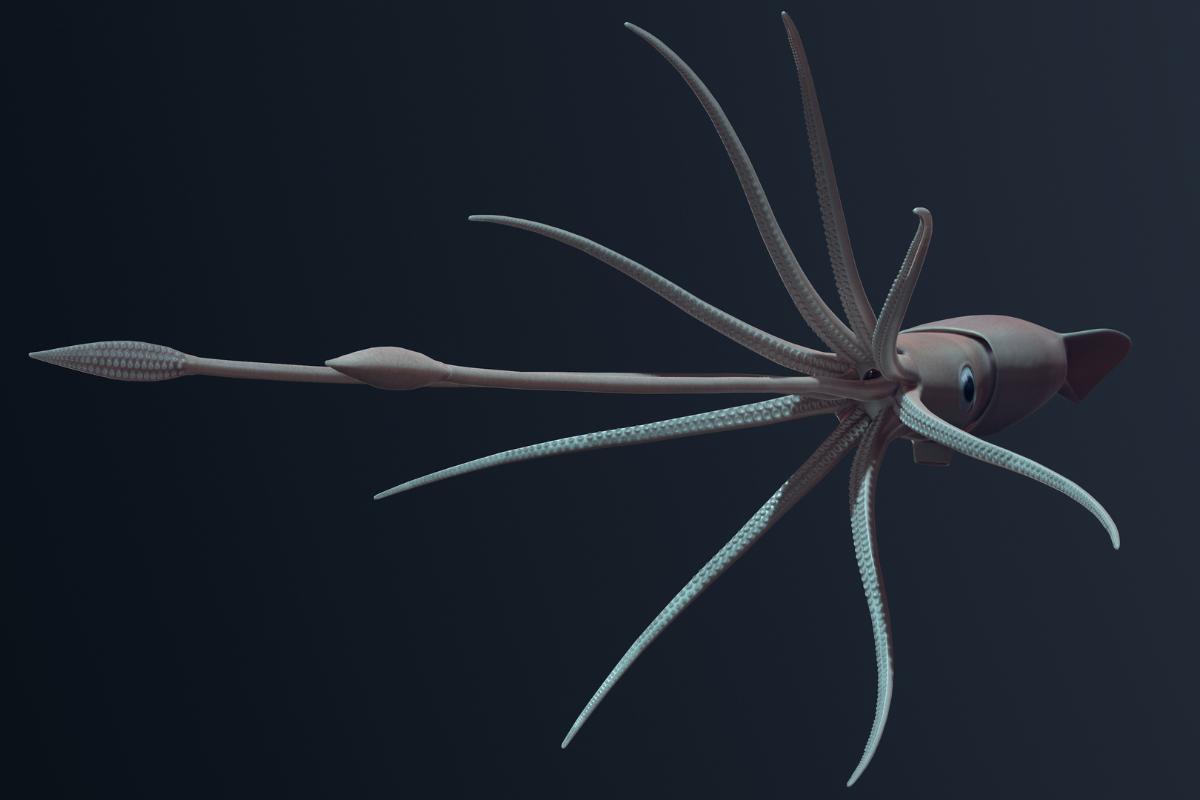

Giant squid (Architeuthis dux)

Giant squids inhabit depths between 300 and 1,000 meters (980 to 3,280 feet) across all oceans, with frequent sightings near Norway, Newfoundland, South Africa, New Zealand, and Japan.

Scientists have documented females reaching 13 meters (43 feet) in length, with males measuring up to 10 meters (33 feet). Most specimens come from accidental findings or when they wash ashore, giving us limited opportunities to study them.

Their adaptation to deep-sea life shows in their anatomy. Their eyes measure 25 centimeters (10 inches) across, the largest in the animal kingdom, allowing them to detect movement in minimal light. Their reddish-brown bodies include a sophisticated buoyancy system for managing extreme pressures.

Giant squids hunt using eight arms and two feeding tentacles equipped with toothed suckers. They catch fish, other squid species, and small whales in their deep-water habitat.

Scientists lack enough data to assess their population status. Current threats include climate change, ocean acidification, pollution, and occasional entanglement in fishing nets. The IUCN lists them as Data Deficient, reflecting how much we still need to learn about these creatures.

While some squids grow impressively large, other marine creatures dwarf even the Giant squid. Meet Earth's largest sea animals in our guide.

Colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni)

The Colossal squid is the heaviest squid species known to science. Current evidence shows they reach about 6 meters (20 feet), but their mass exceeds that of Giant squids. The largest verified specimen weighed 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds).

These squids inhabit Antarctic waters in the Southern Ocean. They live at depths between 1,000 and 2,200 meters (3,280 to 7,220 feet), where temperatures stay close to freezing. The cold, dark environment has influenced their physical features.

Their tentacles have sharp hooks that rotate 360 degrees, something not found in other cephalopods. These swiveling hooks work alongside rows of toothed suckers, making them excellent predators. The muscular arms and tentacles help them catch Antarctic toothfish, other fish species, and smaller squids.

The Colossal squid has specific physical traits. Their eyes, measuring 28 centimeters (11 inches) in diameter, are the largest of any animal. Their mantle contains more muscle mass compared to other squids, resulting in a shorter but wider body that creates their substantial weight.

Scientists list them as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List. Research challenges persist due to their remote habitat and deep-sea location. They face threats from climate change in Antarctic waters and commercial fishing operations that affect their habitat.

If you found the deep-sea squids intriguing, wait until you meet their even stranger neighbors in our guide to the ocean's most unusual fish.

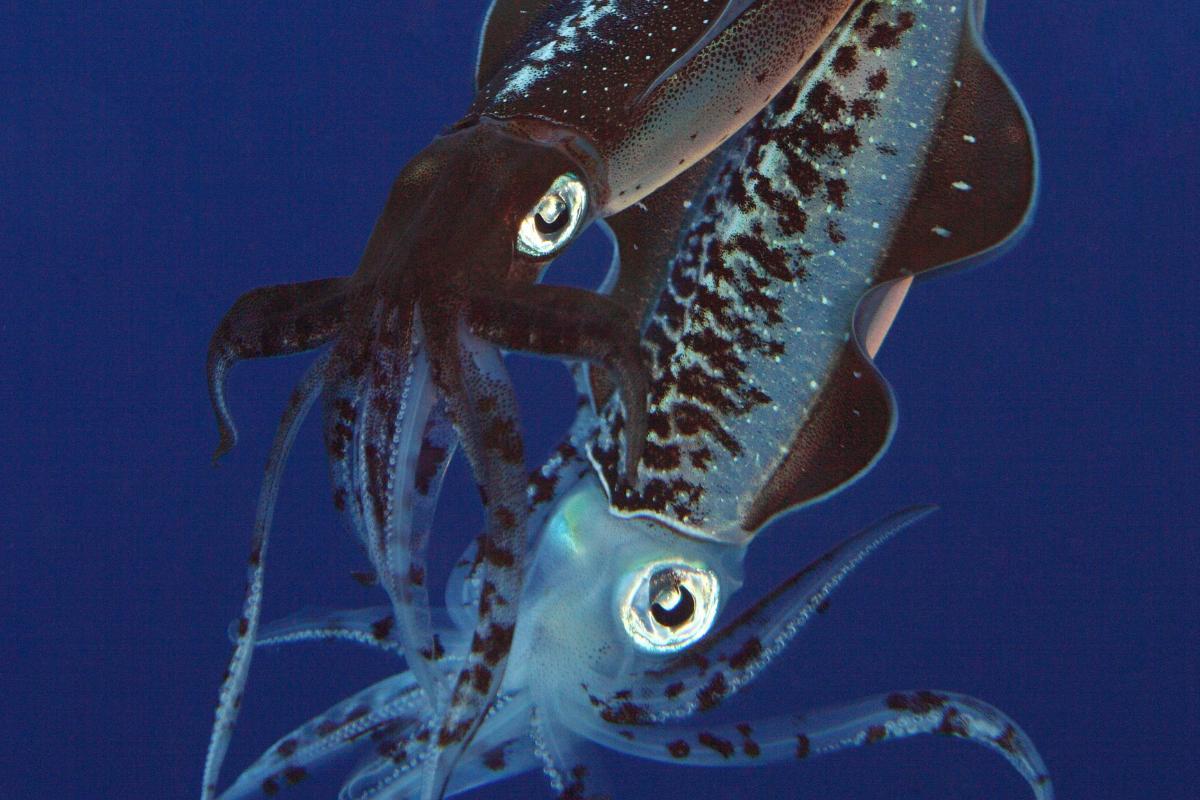

Common squid (Loligo vulgaris)

The common squid, also called the European squid, swims along the coasts of the Eastern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Adults typically measure 20 to 30 centimeters (8 to 12 inches) in mantle length, with some reaching 40 centimeters (16 inches). Males often grow larger than females.

They swim at depths between 0 to 500 meters (0 to 1,640 feet), spending most of their time in the upper 100 meters (330 feet).

They possess chromatophores, which are cells in their skin that expand and contract to create different patterns and colors. The squids use these color changes to hide from predators, communicate with each other, and during mating rituals.

They eat more than scientists first thought. Besides crustaceans and small fish, they hunt other cephalopods and marine worms. They grab prey using their two feeding tentacles and eight arms covered in suckers.

Fisheries across Europe catch these squids in large numbers. While the IUCN hasn't assessed their population status, local fishing regulations help maintain their numbers. However, they face ongoing pressures from commercial fishing and changes in their coastal environments.

Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas)

The Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas), also called the jumbo flying squid or Pacific giant squid, grow up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) in total length, and the heaviest specimens weigh over 50 kilograms (110 pounds).

These squids live in the eastern Pacific Ocean, in an area stretching from Alaska to southern Chile. They move between depths of 200 to 700 meters (660 to 2,300 feet) during their daily vertical migrations. The squids follow the oxygen minimum zone, coming closer to the surface at night to feed.

Their physical traits make them skilled hunters. The squids have strong arms and tentacles lined with sharp-toothed suckers, and their beaks can easily cut through prey. Their body color shifts between deep red and white, earning them the nickname "red devils."

Humboldt squids hunt in groups of 20 to 40 individuals, showing coordinated behavior. Their diet includes fish, crustaceans, and other cephalopods. When food gets scarce, they might eat smaller members of their own species. Each squid can consume up to 10 times its body weight daily.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists them under Least Concern. Their population appears stable, and some areas show increasing numbers. Commercial fishing targets these squids, especially off Chile, Peru, and Mexico, but their fast growth and reproduction rates help maintain their numbers.

Vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis)

The Vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis), also known as the "vampire squid from hell", is actually a gentle filter feeder. These small cephalopods reach about 30 centimeters (12 inches) in length, with females growing slightly larger than males.

They live in the deep ocean's oxygen minimum zones, between 600 and 1,200 meters (1,970 to 3,940 feet) where few other animals survive. Their territory spans temperate and tropical oceans worldwide.

A dark web of skin connects their eight arms, forming a cloak they can wrap around their body when threatened. Unlike typical squids, they lack the two long feeding tentacles. Instead, retractable filaments extend from their arms to catch marine snow, which is the organic matter falling from above.

Their deep-sea life shaped their body structure. Large red eyes detect the faintest light but can't see color. Light-producing organs called photophores dot their skin. When stressed, they release glowing mucus clouds instead of ink.

The IUCN hasn't assessed their numbers yet. While their deep habitat shields them from most human activities, warming oceans and falling oxygen levels could affect where they live.

Pygmy squid (Idiosepius pygmaeus)

The Pygmy squid (Idiosepius pygmaeus) belongs to the smallest family of cephalopods. These tiny creatures measure just 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) in length, about the size of a paper clip.

They inhabit shallow coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific region, from Japan to Australia, living among seagrasses and mangrove roots. A special adhesive gland on their mantle lets them stick to seagrass blades, providing perfect hiding spots from predators. They typically stay in waters no deeper than 20 meters (65 feet).

Their small size comes with advantages. Quick and agile, they catch prey much like their larger relatives. Using their arms and tentacles, they grab tiny crustaceans, fish larvae, and other small marine animals. Their color-changing abilities rival those of other cephalopods, and they are able to match their surroundings in seconds.

Scientists discovered an interesting hunting technique in these squids. They shoot water jets at potential prey, disorienting small shrimp before catching them. This method helps them catch food while staying safely attached to their seagrass hideouts.

The IUCN hasn't evaluated their conservation status. Their coastal habitat makes them vulnerable to water pollution and habitat loss, particularly from damage to seagrass beds and mangrove forests.

Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus)

The Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus) shoots through ocean water and air with equal skill. These squids measure between 20 and 50 centimeters (8 to 20 inches) in mantle length. Like other flying squids, they propel themselves above the water's surface by expelling strong jets of water, reaching heights of 3 meters (10 feet) and distances over 30 meters (100 feet) through the air.

They live throughout the North Pacific, with large populations near Japan, China, and Russia. These squids migrate long distances, following seasonal temperature changes. During winter, they move south to spawn in warmer waters around the Korean Peninsula and Japan. In summer, they head north to rich feeding grounds.

Their bodies help them move fast both underwater and in air. A streamlined mantle and strong muscles let them shoot water with enough force to break the ocean's surface. When airborne, they spread their fins and arms to glide, often traveling in groups. This behavior might help them escape predators or save energy during long migrations.

Their diet goes beyond small fish and invertebrates. They actively hunt lanternfish, anchovies, sardines, and crustaceans. Young squids eat mostly tiny animals called copepods until they grow large enough to catch bigger prey.

Commercial fisheries catch these squids in large numbers, particularly in Japan, South Korea, and China. The IUCN hasn't assessed their status, but their numbers fluctuate yearly based on ocean conditions and fishing pressure. Climate change affecting ocean temperatures might alter their migration patterns and breeding grounds.

Image source: costarica.inaturalist.org

Luminous squid (Watasenia scintillans)

The Luminous squid (Watasenia scintillans), also called the Firefly squid, glows in the darkness of deep waters. These small squids measure about 7 centimeters (2.8 inches) in length.

They live primarily in the western Pacific Ocean, specifically in Japanese waters. During the day, they stay in depths of 200 to 400 meters (656 to 1,312 feet). At night, they swim up to surface waters to feed, creating spectacular light displays in several bays along Japan's coast.

Their bodies contain about 800 light-producing organs called photophores. These organs create blue light at different intensities. The squids use these lights for several purposes, such as attracting prey, communicating with potential mates, and confusing predators. They can control each photophore separately, producing complex patterns of light.

Their hunting strategy involves using their light displays to stun or distract prey before catching it with their tentacles. Besides small crustaceans and fish, they catch krill, copepods, and fish larvae.

Every spring, millions of these squids gather in Toyama Bay, Japan, to spawn. This mass gathering creates an electric blue light show in the water. While the IUCN hasn't assessed their conservation status, their populations face pressure from commercial fishing during spawning season and changes in ocean temperatures that might affect their breeding patterns.

Some squids create their own light displays, but they're not alone. Meet more animals with this amazing ability in our detailed article.

Image source: reinoanimalia.fandom.com

Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidea)

The Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidea) lives in clear, shallow waters. These social cephalopods measure between 20 and 30 centimeters (8 to 12 inches) in length.

They inhabit the western Atlantic Ocean, from Florida to northern Brazil, including the Caribbean Sea. Unlike many other squids, they prefer coral reefs and seagrass beds in waters between 0 to 100 meters (0 to 330 feet) deep. They stay in these areas throughout their lives rather than migrating.

Their social structure involves groups of 4 to 30 individuals. They developed a complex system of skin patterns and colors for communication. Males display different patterns when courting females versus challenging rival males. They can even show different colors on each side of their body, potentially sending separate signals to different squids at once.

Their diet adapts to their reef habitat. They hunt small fish, crustaceans, and mollusks during dawn and dusk when their prey moves between daytime and nighttime shelters.

The IUCN hasn't evaluated their numbers, but local populations face threats from coastal development, pollution, and reef degradation. Their nearshore habitat makes them sensitive to human activities, while warming oceans and coral reef decline might reduce their available living space.

Umbrella squid (Histioteuthis bonnellii)

Umbrella squid (Histioteuthis bonnellii) shows how evolution shaped deep-sea creatures. This squid developed different-sized eyes. Its left eye significantly outgrows its right eye, reaching double the size to catch the faint sunlight from above.

They swim in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, at depths between 200 and 1,000 meters (656 to 3,281 feet). However, they sometimes venture deeper, down to 1,500 meters (4,921 feet). They prefer waters where the continental shelf drops off into deeper ocean.

Their body structure reflects their deep-water lifestyle. Beyond their asymmetric eyes, they have light-producing organs scattered across their body. These photophores create a dim glow that matches downwelling light, helping them hide from predators below. Their skin has a dark reddish-purple color that appears black in deep water, making them harder to spot from above.

Their tentacles have sensitive receptors to detect movement in dark waters, helping them find prey when vision proves limited.

The IUCN hasn't assessed their population status. Living in deep waters generally protects them from direct human impacts, but they might face challenges from warming oceans and increasing ocean acidification, which could affect their prey availability and habitat conditions.

Glass squid family (Cranchiidae)

The Glass squid family (Cranchiidae) earned their name from their see-through bodies. Scientists have identified 65 species across 13 genera, ranging from tiny 10-centimeter (4-inch) specimens to giants stretching 3 meters (10 feet) in length.

They float through all tropical and temperate oceans. While young glass squids stay near the surface, adults swim down to depths of 2,000 meters (6,562 feet). A special chamber in their bodies holds light fluid matching seawater's density, letting them float without using much energy.

Most of their organs cluster in one small area, leaving the rest of their body transparent. The few visible organs hide behind reflective tissue. When danger approaches, some species can tuck their head and arms into their mantle, forming a protective ball shape.

As they grow, their diet shifts. Young glass squids catch plankton, while older ones hunt small fish, crustaceans, and other squid. Despite their slow swimming speed, they can shoot out their two long tentacles to snatch prey.

The IUCN hasn't studied glass squid populations yet. While their widespread presence and deep habitat offer some protection, ocean warming and changing chemistry might harm their delicate bodies.

Image source: twilightzone.whoi.edu

Arrow squid (Nototodarus sloanii)

The Arrow squid (Nototodarus sloanii) speeds through New Zealand's waters and the South Pacific. These agile swimmers reach up to 50 centimeters (20 inches) in length, though most adults measure between 20 to 40 centimeters (8 to 16 inches).

They move between the surface and depths of 500 meters (1,640 feet) around New Zealand, the southern coast of Australia, and nearby Pacific islands. Their seasonal migrations follow water temperature changes and food availability. During summer, they gather in shallower coastal waters to breed. In winter, they swim to deeper offshore waters.

Their streamlined bodies help them reach high speeds, making them skilled hunters. Two rows of strong suckers line their arms and tentacles, perfect for catching slippery prey.

These squids play a key role in their ecosystem. They feed larger animals like seabirds, seals, and dolphins while controlling populations of smaller marine creatures.

The IUCN hasn't evaluated their conservation status. However, scientists monitor their populations closely because they support important commercial fisheries. Climate change might affect their migration patterns and breeding success, as warming waters could shift their preferred temperature zones.

Image source: diark.org

If you want to read similar articles to Different Types of Squid, we recommend you visit our Facts about the animal kingdom category.

Guerra, A., González, Á. F., Pascual, S., & Dawe, E. G. (2020). The giant squid Architeuthis: An emblematic invertebrate that can represent concern for the conservation of marine biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 244, 108559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108559

- Villanueva, R., Perricone, V., & Fiorito, G. (2017). Cephalopods as predators: A short journey among behavioral flexibilities, adaptions, and feeding habits. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 598. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00598

- Zeidberg, L. D. (2021). Advances in the life history and ecology of jumbo squid. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 31(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-020-09625-9