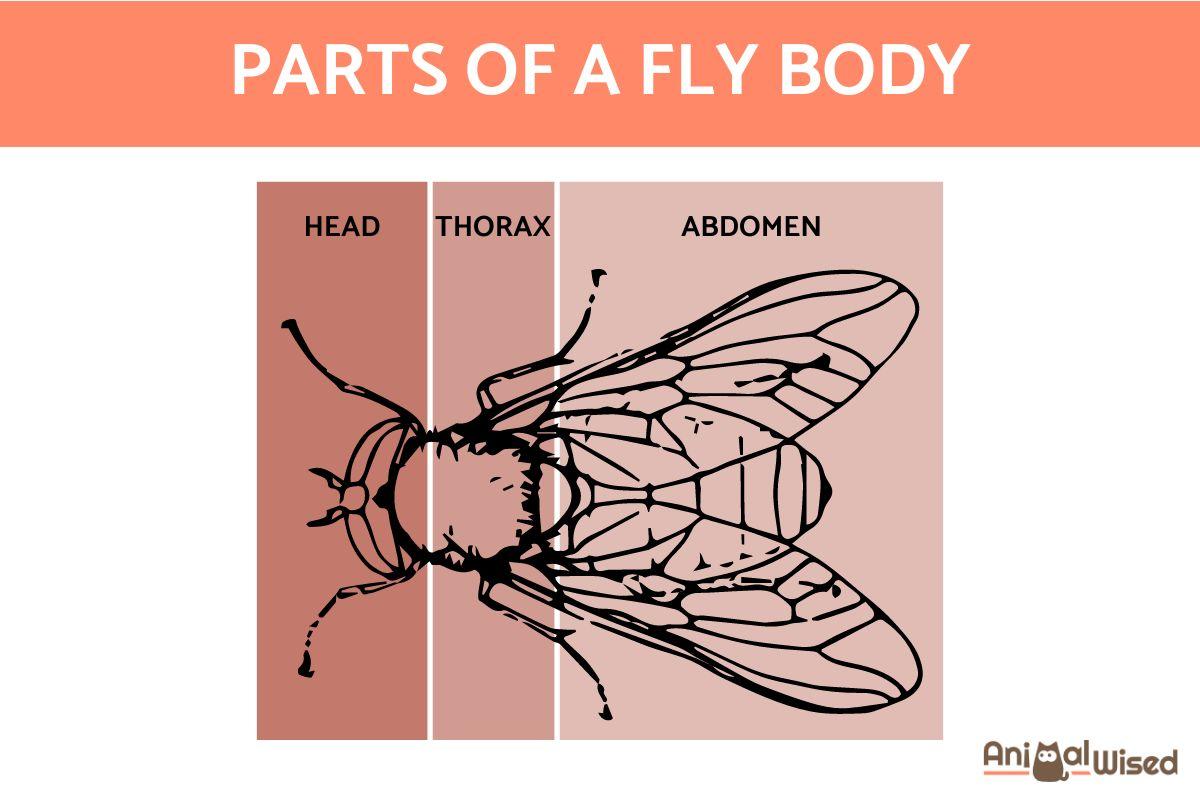

Parts of a Fly Body

Belonging to the order Diptera, this incredibly diverse group encompasses a vast array of species, from the familiar housefly to the bizarre botfly. But what allows these insects to thrive in such a wide range of environments? The key lies in their fascinating anatomy. Their bodies are segmented into three distinct regions, each packed with specialized structures that enable them to survive and reproduce.

This AnimalWised article will delve into the intricate anatomy of a fly's body, explaining how each part functions.

Head

The head of a fly, in biology, is called the capitulum. It is a highly specialized structure crucial for sensory perception, feeding, and environmental interaction and contains several important structures that are essential for the fly's survival, such as the eyes, antennae and mouthparts:

Compound eyes

Flies have a unique type of eye called a compound eye. Unlike our eyes, which have a single lens that focuses light onto a retina, a compound eye is made up of thousands of tiny lenses, called ommatidia, each working like a miniature eye. These eyes offer a panoramic view, enabling flies to detect rapid movements and light changes with great sensitivity. Compound eyes are also very good at detecting movement. This is because even small changes in light hitting one or two ommatidia can be detected by the fly's brain.

Antennae

Flies, like most insects, rely heavily on their antennae for navigating the world. They are highly sensitive sensory organs for detecting odors and chemical stimuli. These antennae are segmented and covered with sensilla, tiny sensory hairs containing chemoreceptors and mechanical receptors. Flies typically have a pair of antennae, which are segmented. The number of segments, as well as the shape and size of fly antennae, can vary depending on the fly species and its specific needs.

They play a vital role in detecting pheromones, food, mates, and potential threats, varying in shape and structure across species.

Oral structures

Flies don't have jaws for chewing like we do, instead, their mouthparts (called proboscis) are adapted for specific feeding strategies depending on the fly species, feeding habits and diet.

Instead of chomping down on food, a fly's proboscis is like a multi-tool for specialized feeding. The basic structure consists of several parts:

- Labellum:spongy lower lip

- Labrum: upper lip

- Maxillae: sensory and food manipulation

- Mandibles: mostly vestigial in most flies

Some flies have proboscises for piercing and sucking liquids, while others feed on decomposing matter or plant pollen. Despite differences, all mouthparts facilitate feeding on a range of food sources, including liquids, solids, and decaying tissues.

We explore the mystery of fly sleep in our related article. Keep reading to discover their unique habits.

Thorax

The thorax of a fly is specially adapted for flight. Unlike our own chests, the fly's thorax is the most rigid and segmented part of its body.

The thorax is divided into three segments: the prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax. Each segment has plates (sclerites) that provide a strong and lightweight external skeleton.

The mesothorax is the most important segment for flight. It houses powerful muscles called indirect flight muscles that take up most of the space. These muscles are asynchronous, meaning they can contract and relax very quickly, enabling the rapid wing beating necessary for flight.

The mesothorax and metathorax are where the wings attach to the fly's body. Small muscles in these segments provide precise control over wing movement during flight. Some flies, like houseflies, also have a smaller second pair of wings called halteres that help with stability.

Wings

Unlike bird wings, fly wings are not rigid. They are thin, membranous structures with veins that provide support and shape. These veins are similar to the bones in our limbs, but much lighter and more flexible. They are hollow tubes filled with hemolymph (insect equivalent of blood) and can be arranged in complex patterns depending on the fly species.

The shape and size of the wings play a crucial role in flight. Fly wings are typically flat and oval-shaped, creating an airfoil that generates lift as the fly beats its wings.

The specific wingbeat pattern also affects flight. Flies can rapidly beat their wings, sometimes thousands of times per second, which allows for quick changes in direction and hovering. Some fly species can even fly backwards.

There's some variation in fly wing design depending on the fly's needs. Houseflies, for example, have two well-developed wings for efficient flight. Mosquitoes have a single pair of flight wings for forward flight, and smaller hindwings called halteres that act like gyroscopes for stability.

We've explored their parts, but can they bite? Delve deeper into the world of flies and discover if they pose a threat in our related article.

Abdomen

The abdomen of a fly is the multi-functional rear section of the fly's body. It is also the largest and most flexible part and consists of multiple segments (usually 11) called urities, which are connected by flexible membranes.

Each urite has a dorsal plate (tergum) on top and a ventral plate (sternum) below, offering some protection for the internal organs while allowing for flexibility in movement.

Digestive system

The abdomen houses the fly's digestive system, including the stomach, intestines, and associated organs. Here, food is broken down and nutrients are absorbed. The excretory system, responsible for waste removal, is also housed in the abdomen.

Respiratory system

The respiratory system, including tracheae and spiracles, is located in the abdomen. Tracheae are branching tubes facilitating gas exchange throughout the body, while spiracles allow air entry and carbon dioxide exit. This system ensures oxygen supply to cells and removal of metabolic waste.

Nervous system

While the head contains the main brain, the abdomen has a network of nerves that coordinate movement, digestion, and other functions in the rear part of the body.

Reproductive organs

The reproductive organs are also located in the abdomen. In females, this includes ovaries and egg-laying structures. Males have testes and structures for sperm transfer.

Sensory organs

The abdomen may contain specialized sensory organs like sensilla, vibration receptors, and chemoreceptors. These organs enable flies to detect environmental changes, aiding in predator avoidance, food detection, and mate selection.

The shape and size of the abdomen can vary depending on the fly species and its sex. For example, female mosquitoes have a more elongated abdomen to accommodate developing eggs.

Ever wondered why flies constantly groom themselves? Unravel the fascinating reason behind their leg-rubbing behavior in our related article.

If you want to read similar articles to Parts of a Fly Body, we recommend you visit our Facts about the animal kingdom category.

- Christenson, L.D., & Foote, R.H. (1960). Biology of fruit flies . Annual review of entomology, 5(1), 171-192.

- Graham-Smith, G. S. (1930). Further observations on the anatomy and function of the proboscis of the blow-fly, Calliphora erythrocephala L. Parasitology, 22(1), 47-115.

- Lowne, B. T. (1895). The Anatomy, Physiology, Morphology and Development of the Blow-fly: (Calliphora Erythrocephala.) A Study in the Comparative Anatomy and Morphology of Insects; with Plates and Illustrations Executed Directly from the Drawings of the Author (Vol. 2).