How Do Whales Breathe?

Whales belong to a group of marine mammals known as Cetacea. As mammals, whales also have lungs, just like us, and breathe air, just like us. Most people believe that whales are a type of fish because they are perfectly adapted to life underwater. However, this is not true at all. Whales are warm-blooded, breathe air through lungs, and give birth to live young that feed on their mother's milk.

The following AnimalWised article explains how whales breathe, the evolutionary adaptations they have undergone, and how they sleep without drowning.

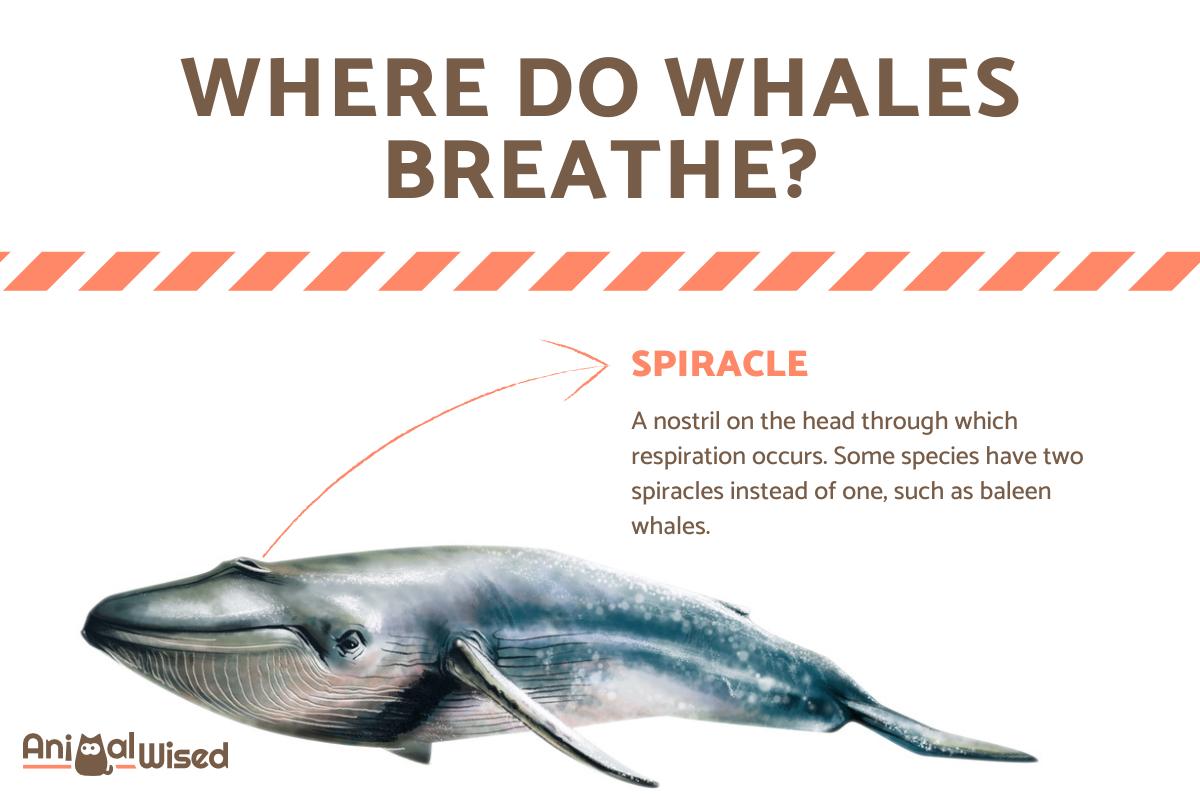

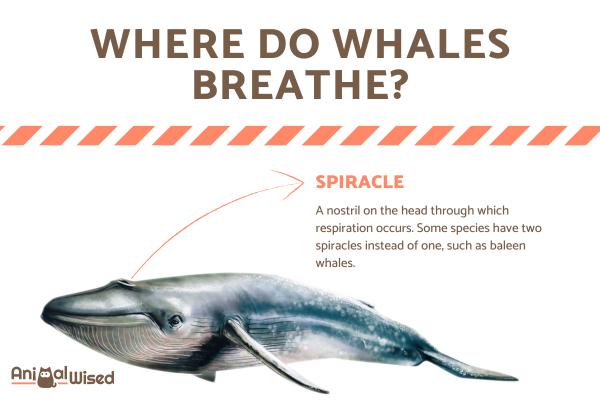

Where do whales breathe?

Whales breathe through spiracles, also called blowholes. These are basically the nostrils of whales and other cetaceans. Spiracles gradually evolved into being located at the top of the head. The location of these openings allows whales to minimize the energy required to breathe at the water surface. Not all whale species have the same number of spiracles. For example, baleen whales have two spiracles, while toothed whales only have one.

Whales cannot breathe through their mouths because they have isolated channels for breathing and feeding. Therefore, they can eat without water entering their lungs.

When whales dive underwater, their nasal plug covers the nasal passage to the blowhole. The muscles that control the nasal plug are relaxed during this time. These muscles contract when the whale gasps for air, opening the blowhole and allowing it to exhale and inhale.

How do whales breathe?

The breathing of whales is very efficient, and they have conscious control over their breathing and pulse. The ability to regulate their oxygen levels is especially important for species that dive deep. Underwater, they can slow their pulse and direct oxygen-rich blood to areas that need it, such as the brain, heart, and muscles.

The short time they spend at the surface forces them to exchange CO2 for O2 very quickly, which is why gas exchange in marine mammals is bidirectional. Gas exchange takes place in the alveoli, the sac-like extensions of the lungs.

Whales and dolphins can expel air both underwater and at the surface. In the former case, the air reaches the surface in the form of bubbles. Curiously, some whales use these bubbles to catch fish in "bubble nets" so that other whales can benefit. In the second case, however, the air is already expelled at the surface since the supply of new oxygen can only occur outside the water.

The time whales can hold their breath underwater depends on the species. Sperm whales can hold their breath for up to 90 minutes, while other species, such as Cuvier's beaked whales, can hold their breath for more than two hours.

If you want to learn more about aquatic mammals, do not miss this other article, where we talk about their main characteristics and describe some of the most known species.

The breathing process of whales

The breathing process of whales begins with the expulsion of CO2. In the water, we have already seen that they do this in the form of bubbles. Out of the water, however, they expel a large amount of air and water through the blowhole. The blowing sounds that are so characteristic of whales are produced by the rapid emptying of the lungs.

This emptying occurs so quickly because they have a much more flexible chest wall and very strong pectoral muscles that allow them to compress the lungs until they are virtually empty. When the warm air from the whale's lungs meets the cold air outside, it condenses into a cloud, as if we were watching our breath on a cold day. This cloud also contains mucus and seawater droplets that cover the blowhole when the whale exhales.

This also allows them to store as much oxygen as possible to use during the dive. Blue whales are able to empty and refill their 1,500 liter lungs in just 2 seconds. This snorting exhale is followed by a much slower inhale, followed by complete airway closure and apnea.

Contrary to what one might expect, cetacean lungs are not larger (in terms of relative size) than those of land mammals. However, they have a much higher tidal volume, which means they are capable of much deeper inhalations and exhalations. The breathing patterns of cetaceans vary greatly depending on the behavior and activity of each species.

During their large dives, the alveoli that make up the whales' lungs are in danger of collapsing due to the high pressure. Therefore, at a depth of 50-100 meters, all the air in the lungs is compressed by the powerful muscles, leading all the alveolar air to the bronchioles and trachea of the lungs, which are much more resistant than the alveoli. In this way, part of the oxygen is also absorbed by compressing the air in the alveoli, giving them an additional supply at depth.

If you are interested in whales, you might be interested in this other article where we talk about which are the largest whales in the world and how big they are.

Other adaptations associated with the breathing of whales

In addition to the respiratory system adaptations mentioned earlier, cetaceans, and in this case whales, have also developed other methods to help them breathe more efficiently.

- Whales have a network of blood vessels in the animal's thoracic cavity and extremities that serve as a reservoir for oxygen-rich blood supplied during diving.

- The whales' red blood cells can also carry more oxygen.

- When diving, whales' blood flows only to the parts of the body that need oxygen, such as the heart, brain and swimming muscles. Digestion and all other processes have to wait.

- Whales also have a higher tolerance to carbon dioxide (CO2). Their brains do not trigger a breathing response until CO2 levels are much higher than what other terrestrial mammals can tolerate. These mechanisms, which are part of the marine mammals' diving response, are adaptations to living in an aquatic environment and help them sleep.

If you want to learn more about whales, do not miss this other article where we discuss the different types of whales.

How do whales sleep without drowning?

Because marine mammals cannot breathe underwater, they rarely drown, although they can suffocate if their air supply is inadequate. To avoid this, whales must come to the surface to breathe while they sleep.

To overcome this problem, whales have a very light sleep called unhemispheric slow-wave sleep (USWS). In USWS, also called asymmetric slow-wave sleep, one half of the brain rests while the other half remains alert. This is in contrast to normal sleep, where both eyes are shut and both halves of the brain show unconsciousness. After about two hours, the animal reverses this process by resting the active side of the brain and awakening the resting half.

Scientists believe this behavior helps animals avoid predators, socialize, control breathing or continue swimming.

Are the sleeping habits of whales in captivity and in the wild identical?

Recently, photos have surfaced on the Internet showing groups of sperm whales that appear to be standing upright and not moving in groups of five or six. This behavior was previously unknown to scientists because most studies of cetacean sleep have been conducted on cetaceans in captivity.

More recent studies on wild whales have found that whales spend seven percent of their day in these upright positions near the surface of the water, where they sleep for 10 to 15 minutes. These studies even suggest that some whales in the wild might be deep sleepers, unlike their captive relatives. This hypothesis is based on a video taken off northern Chile that shows that the whales only awoke from their sleep when an approaching boat with its engine off accidentally collided with them.

You can learn more about animals' sleeping habits in this other article, where we discuss whether there are any animals that do not sleep.

If you want to read similar articles to How Do Whales Breathe?, we recommend you visit our Facts about the animal kingdom category.

- Berta, A., Sumich, J.L., & Kovacs, KM (2005). Marine mammals: evolutionary biology . 3rd edition. Elsevier.

- Lyamin, OI, Manger, PR, Ridgway, SH, Mukhametov, LM & Siegel, JM (2008). Cetacean sleep: an unusual form of mammalian sleep . Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32, 1451-1484.

- Ponganis, P.J. (2015). Diving physiology of marine mammals and seabirds . Cambridge University Press.