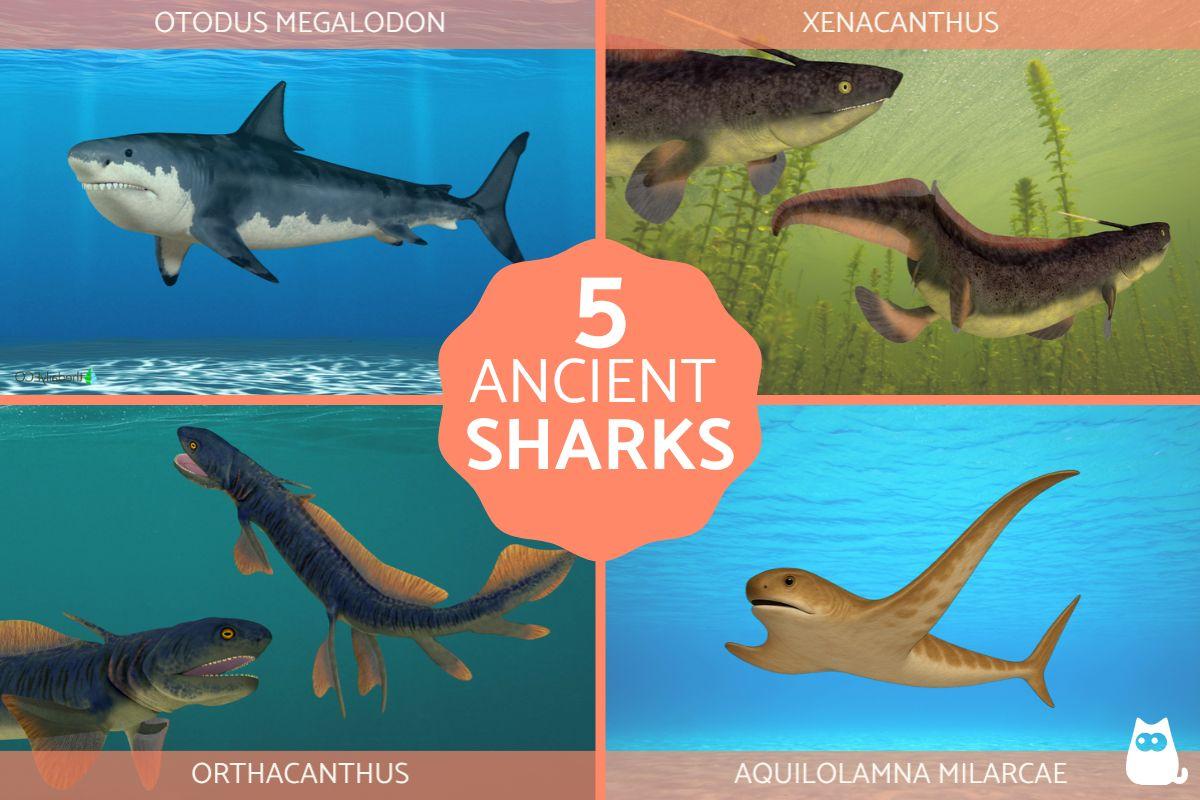

5 Extinct Prehistoric Sharks

Sharks have been a dominant force in marine ecosystems for over 400 million years. Originating in the Paleozoic Era, these resilient predators survived multiple mass extinctions, evolving into a spectacular variety of prehistoric forms. Among them were ancient sharks with incredible adaptations for hunting and survival.

This AnimalWised article will introduce you to 5 examples of these extinct prehistoric sharks. We'll delve into what made them unique, their key physical features, the time periods they inhabited, and their evolutionary significance in the grand narrative of shark history.

How do we know about prehistoric sharks?

Studying prehistoric sharks presents unique challenges for scientists. Unlike dinosaurs with their bones, sharks have skeletons made primarily of cartilage, which is the same flexible material found in human ears and noses. The main problem is that this cartilage rarely fossilizes, which makes complete shark fossils extremely uncommon.

As a result, scientists have to piece together the story of prehistoric sharks mainly through four types of fossilized remains:

- Teeth: they are the most abundant shark fossils by far. Shark teeth are highly mineralized and durable, allowing them to survive for millions of years. A single shark can shed thousands of teeth in its lifetime, creating many opportunities for fossilization.

- Scales: also called dermal denticles, these tooth-like scales covered sharks' bodies and occasionally fossilize. The oldest known shark scales date back 420 million years.

- Vertebrae: though are also cartilaginous, the central parts of shark vertebrae sometimes contain enough minerals to fossilize. These rare finds help scientists estimate body sizes and shapes.

- Fin spines and cranial cartilages: occasionally, parts of fins or skull structures preserve well enough to provide insights into prehistoric sharks' appearance and lifestyle.

Despite these limitations, fossil evidence reveals that prehistoric sharks were remarkably diverse. Scientists estimate that ancient oceans contained twice as many shark species as exist today.

These earliest sharks differed from modern forms in several important ways:

- Many possessed double-cusped teeth instead of the specialized cutting teeth we see in today's species.

- Their snouts were typically more rounded, while their brains were proportionally smaller compared to body size.

- Their fins had less flexibility than modern sharks, which likely affected their swimming abilities.

Throughout all these variations, however, the basic cartilaginous skeleton has remained a consistent hallmark of shark design for hundreds of millions of years.

To show you just how diverse prehistoric sharks were, we've picked five extinct species. Each one offers a unique look at a different time period and a different way of life in the ancient seas.

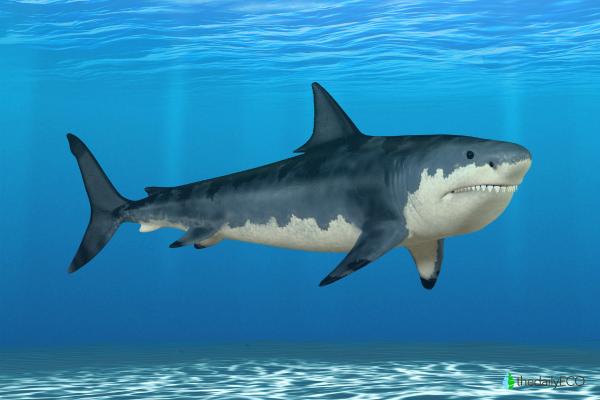

1. Otodus megalodon

When it lived:

Megalodon swam the ancient oceans from 23 to 3.6 million years ago, during the Early Miocene to Early Pliocene epochs.

Size and appearance:

Megalodon was the largest shark that ever lived, growing to an incredible length of 50 to 60 feet, which is roughly the size of a bowling lane. This enormous predator had a robust, muscular body with a relatively short snout and powerful jaws filled with serrated, triangular teeth that could reach the size of a human hand (up to 7 inches tall).

While no complete skeleton has ever been found, scientists believe it resembled a much larger version of today's predatory sharks, with strong swimming capabilities and a streamlined shape.

Hunting and diet:

As the top predator in ancient oceans, megalodon primarily hunted large marine mammals, including prehistoric whales, seals, and sea lions. Fossil whale bones bearing distinctive megalodon tooth marks show evidence of powerful, crushing bites that could sever spines and shatter rib cages.

Its hunting strategy likely involved targeting vital areas like flippers and tails to immobilize prey before delivering a killing bite. This is a strategy still used by great white sharks today, though on much smaller prey.

Habitat:

Megalodon inhabited warm, shallow waters along continental coastlines worldwide. Fossils have been discovered on every continent except Antarctica, indicating it had a global distribution in tropical and temperate oceans. Unlike some deep-water sharks, megalodon likely stayed relatively close to shore, where large marine mammals were abundant.

Evolutionary relationships:

Scientists once thought megalodon was a direct ancestor of today's great white shark due to similarities in their teeth. However, modern research shows that megalodon belonged to a different shark family (Otodontidae) that has no living members.

The similarities between megalodon and great white sharks resulted from convergent evolution, where unrelated species independently evolve similar features because they occupy similar ecological roles.

Extinction:

Megalodon disappeared around 3.6 million years ago as Earth's climate cooled, sea levels dropped, and many shallow coastal areas disappeared. These changes affected the availability of its prey and possibly its breeding grounds. Competition from newly evolved predators like killer whales may have further contributed to its extinction.

2. Xenacanthus

When it lived:

Xenacanthus inhabited Earth's freshwater environments from 380 to 225 million years ago, during the Late Devonian to Early Triassic periods

Size and appearance:

Unlike most sharks, Xenacanthus lived exclusively in freshwater environments.

Growing to about 3-4 feet in length, it had an eel-like body with its most distinctive feature being a long, sharp spine that protruded from the back of its head. This spine pointed backward and likely served as protection against predators.

Hunting and diet:

These freshwater sharks were ambush predators that likely hid among vegetation in rivers, lakes, and swamps. They fed primarily on small fish, ancient amphibians, and aquatic invertebrates. Their unique teeth were specially adapted for catching and holding onto slippery prey in freshwater environments where visibility was often poor.

Habitat:

Xenacanthus thrived in freshwater environments including rivers, lakes, and swamps. Fossil evidence suggests they were adapted to low-oxygen, shallow waters that might have been too challenging for many other predators. Their fossils have been found primarily across what is now Europe and North America.

Evolutionary significance:

Xenacanthus belonged to an early divergent lineage of sharks that evolved specialized adaptations for freshwater environments. This group demonstrates that early sharks were actually more ecologically diverse than modern sharks, having conquered habitats that their descendants would later abandon.

Extinction:

These unusual sharks disappeared by about 225 million years ago, coinciding with the end-Permian mass extinction, the most severe extinction event in Earth's history. This catastrophic event wiped out approximately 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species and 90% of marine species.

Want to understand what makes sharks such perfect predators? Dive deeper into the incredible engineering behind these ocean hunters in our comprehensive guide to shark physiology.

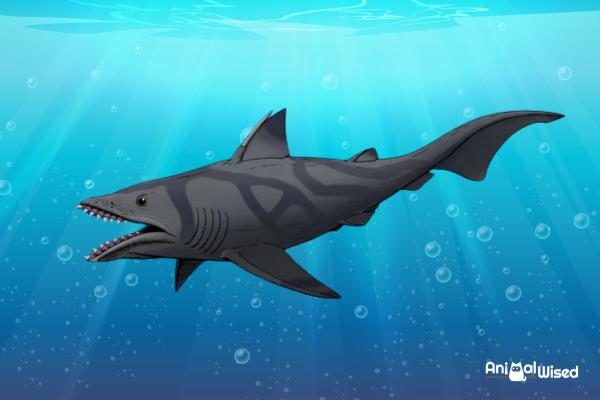

3. Orthacanthus

When it lived:

Orthacanthus dominated freshwater ecosystems from 359 to 270 million years ago, during the Carboniferous to Early Permian periods.

Size and appearance:

Orthacanthus was also a freshwater predator that could reach lengths of up to 10 feet, comparable to a modern-day great white shark. Like its smaller relative Xenacanthus, it had an eel-like body with a spine protruding from the back of its head.

Its teeth had three points arranged in a trident pattern, with a larger central cusp flanked by two smaller ones. This arrangement created an effective tool for grabbing and holding onto prey in murky freshwater environments.

Hunting and diet:

As one of the largest predators in ancient freshwater ecosystems, Orthacanthus sat at the top of the food chain. It fed on amphibians, other fish, and even smaller members of its own species. This behavior may have been a survival strategy during times of food scarcity in seasonal wetlands.

Habitat:

Orthacanthus inhabited prehistoric rivers, swamps, and lakes during a time when vast coal-forming wetlands dominated many landscapes. These freshwater environments supported diverse ecosystems, with Orthacanthus serving as the apex predator. Fossils have been found primarily in coal deposits in what is now Europe and North America, particularly in the United Kingdom, Germany, and the eastern United States.

Evolutionary significance:

As one of the largest members of the freshwater shark group Xenacanthiformes, Orthacanthus demonstrates that sharks once dominated freshwater ecosystems just as effectively as they later would the oceans.

Extinction:

The genus disappeared during the late Permian period, approximately 270 million years ago, before the end-Permian mass extinction event. Climate changes affecting freshwater habitats and competition from evolving amphibian and early reptile groups may have contributed to its decline.

Fascinated by megalodon's massive size? While this giant is extinct, several enormous sharks still patrol today's oceans. Discover the ocean's current titans in our guide to modern-day marine giants.

4. Elegestolepis

When it lived:

Elegestolepis swam in ancient seas from 425 to 400 million years ago, during the Late Silurian to Early Devonian periods.

Size and appearance:

Elegestolepis is one of the earliest known sharks, swimming in ancient oceans over 400 million years ago. Unfortunately, scientists know very little about its complete appearance because Elegestolepis is known primarily from isolated scales rather than complete specimens. Based on these limited remains, researchers believe it was likely a small to medium-sized shark with a body plan more primitive than later species.

Habitat:

Based on where its fossils have been found, Elegestolepis appears to have inhabited shallow marine environments. Beyond this basic habitat information, details about its specific ecological niche remain uncertain due to the fragmentary nature of the fossil evidence.

Evolutionary significance:

Elegestolepis represents one of the earliest definitive examples of a shark-like fish. It helps establish that the basic shark body plan had already begun to evolve over 400 million years ago, long before the rise of dinosaurs or even the first land animals.

Its scales show a transitional structure between those of even more primitive jawless fish and those of later sharks. These tiny fossilized scales provide a rare window into the very beginning of the shark lineage, helping scientists understand how the earliest sharks were adapting and evolving.

Extinction:

The genus is not found in deposits younger than Early Devonian (approximately 400 million years ago), suggesting it either went extinct or evolved into different forms as shark diversity expanded during the Devonian period, often called the "Age of Fishes."

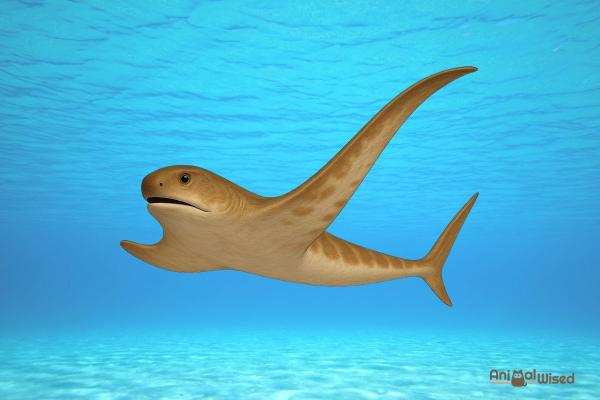

5. Aquilolamna milarcae

When it lived:

Aquilolamna milarcae glided through ancient seas 93 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period (Turonian stage).

Size and appearance:

Discovered only recently and described in 2021, Aquilolamna represents one of the most unusual sharks ever found.

Nicknamed the "eagle shark," it combined features never before seen together in a single animal. Its body measured about 5.4 feet (1.65 meters) long with a wingspan of approximately 6.2 feet (1.9 meters) created by extremely elongated, wing-like pectoral fins. This made the shark actually wider than it was long.

While its torpedo-shaped body and asymmetrical tail resembled those of typical sharks, its enormous wing-like fins were unlike anything seen in other shark species.

Feeding and swimming:

Though no teeth were preserved in the fossil, the shark's broad head and wide mouth suggest it was likely a filter feeder, straining tiny plankton from the water similar to today's whale sharks and manta rays.

Unlike manta rays that "fly" through the water by flapping their fins, Aquilolamna probably used its wing-like fins for stability and gentle gliding while propelling itself forward with its tail.

Habitat:

Aquilolamna inhabited open marine environments during the Late Cretaceous period, when much of Mexico was covered by a shallow sea. It lived in the same waters as marine reptiles, ammonites, and various bony fishes.

Evolutionary significance:

Aquilolamna represents a previously unknown evolutionary experiment in shark design. Its unique body plan shows that prehistoric sharks evolved a much wider range of forms and lifestyles than scientists previously realized.

It appears to have independently evolved a body shape somewhat similar to rays, despite belonging to an entirely different lineage, another example of convergent evolution.

Extinction:

This unusual shark lineage seems to have disappeared by the end of the Cretaceous period, possibly during the mass extinction event that also claimed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. No similar forms are known from later time periods.

Did you know that some modern shark species can live for centuries? Explore the remarkable age-defying abilities of these ocean predators in our in-depth article on shark longevity.

If you want to read similar articles to 5 Extinct Prehistoric Sharks, we recommend you visit our Facts about the animal kingdom category.

- Cappetta, H., Morrison, K., & Adnet, S. (2019). A shark fauna from the Campanian of Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada: An insight into the diversity of Cretaceous deep-water assemblages. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 518, 97-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.01.022

- Compagno, L. J. V. (2002). Sharks of the world: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/3/x9293e/x9293e00.htm

- Cooper, J. A., Pimiento, C., Ferrón, H. G., & Benton, M. J. (2020). Body dimensions of the extinct giant shark Otodus megalodon: A 2D reconstruction. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 14596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71387-y

- Ebert, D. A., & Compagno, L. J. V. (2009). Chlamydoselachus africana, a new species of frilled shark from southern Africa (Chondrichthyes, Hexanchiformes, Chlamydoselachidae). Zootaxa, 2173(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2173.1.1